The comprehensive plan is the adopted official statement of a local government’s legislative body for future development and conservation. It sets forth goals such as analyse existing conditions and trends, describes and illustrates a vision for the physical, social and economic characteristics of the community in the years ahead and outlines policies and guidelines intended to implement that vision. Comprehensive plans address a broad range of interrelated topics in a unified way. A comprehensive plan identifies and analyses the important relationships among the economy, transportation, community facilities and services, housing, environment, land use, human services and other community components. It does so on a communitywide basis and in the context of a wider region.

A comprehensive plan addresses the long-range future of a community, using a time horizon up to 20 years or more. The most important function of a comprehensive plan is to provide valuable guidance to those in the public and private sector as decisions are made affecting the future quality of life of existing and future residents and the natural and built environments in which they live, work and play. All states have enabling legislation that either allow or require, local governments to adopt comprehensive plans. In some states, the enabling legislation refers to them as General plans. Most state-enabling legislation describes generally what should be included in a comprehensive plan.

Reasons to Prepare a Comprehensive Plan

1) View the “Big Picture”

The local comprehensive planning process provides a chance to look broadly at programs on housing, economic development, public infrastructure and services, environmental protection, natural and human-made hazards and how they relate to one another. A local comprehensive plan represents a “big picture” of the community related to trends and interests in the broader region and in the state in which the local government is located.

2) Coordinate Local Decision Making

Local comprehensive planning results in the adoption of a series of goals and policies that should guide the local government in its daily decisions. For instance, the plan should be referred to for decisions about locating, financing and sequencing public improvements, devising and administering regulations such as zoning, subdivision controls and redevelopment. In so doing, the plan provides a way to coordinate the actions of many different agencies within local government.

3) Give Guidance to Landowners and Developers

In making its decisions, the private sector can turn to a well-prepared comprehensive plan to get some sense of where the community is headed in terms of the physical, social, economic and transportation future. Because comprehensive planning results in a statement of how local government intends to use public investment and land development controls, the plan can affect the decisions of private landowners.

4) Establish a Sound Basis in Fact for Decisions

A plan, through required information gathering and analysis, improves the factual basis for land use decisions. Using the physical plan as a tool to inform and guide these decisions establishes a baseline for public policies. The plan thus provides a measure of consistency to governmental action, limiting the potential for arbitrariness.

5) Involve a Broad Array of Interests in a Discussion about the Long Range Future

Local comprehensive planning involves the active participation of local elected and appointed officials, line departments of local government, citizens, the business community, nongovernmental organizations and faith based groups in a discussion about the community’s major physical, environmental, social or economic development problems and opportunities. The plan gives these varied interests an opportunity to clarify their ideas, better envisioning the community they are trying to create.

6) Build an Informed Constituency

The plan preparation process, with its related workshops, surveys, meetings and public hearings, permits two-way communication between citizens and planners and officials regarding a vision of the community and how that vision is to be achieved. In this respect, the plan is a blueprint reflecting shared community values at specific points in time. This process creates an informed constituency that can be involved in planning initiatives, review of proposals for plan consistency and collaborative implementation of the plan.

Plan Elements

The scope and content of state planning legislation varies widely from state to state with respect to its treatment of the comprehensive plan. Required elements include:

- Land use

- Transportation

- Community facilities (includes utilities and parks and open space)

- Housing

- Economic development

- Critical and sensitive areas

- Natural hazards

- Agricultural lands

Optional elements addressing urban design, public safety and cultural resources may also be included. Moreover, the suggested functional elements are not intended to be rigid and inflexible. Participants in the plan process should tailor the format and content of the comprehensive plan to the specific needs and characteristics of their community. The level of detail in the implementation program will vary depending on whether such actions will be addressed in specific functional plans. The various plan elements are explained below.

1) Issues and Opportunities Element

The issues and opportunities element articulates the values and needs of citizens and other affected interests about what the community should become. The local government then interprets and uses those values and needs as a basis and foundation for its planning efforts. An issues and opportunities element should contain seven items.

- A vision or goals and objectives statement

- A description of existing conditions and characteristics

- Analysis of internal and external trends and forces

- A description of opportunities, problems, advantages and disadvantages

- A narrative describing the public participation process

- The legal authority or mandate for the plan

- A narrative describing the connection to all the other plan elements

2) Vision or Goals and Objectives Statement

This statement is a formal description of what the community wants to become. It may consist of broad communitywide goals, may be enhanced by the addition of measurable objectives for each of the goals or may be accompanied by a narrative or illustration that sets a vision of the community at the end of the plan period.

3) Existing Conditions and Characteristics Description

This description creates a profile of the community, including relevant demographic data, pertinent historical information, existing plans, regulatory framework and other information that broadly informs the plan. Existing conditions information specific to a plan element may be included in that elements within the plan.

4) Trends and Forces Description

This description of major trends and forces is what the local government considered when creating the vision statement and considers the effect of changes forecast for the surrounding region during the planning period.

5) Opportunities, Problems, Advantages and Disadvantages

The plan should include a statement of the major opportunities, problems, advantages and disadvantages for growth and decline affecting the local government, including specific areas within its jurisdiction.

6) Public Participation

The summary of the public participation procedures describes how the public was involved in developing the comprehensive plan.

7) Legal Authority or Mandate

This brief statement describes the local government’s legal authority for preparing the plan. It may include a reference to applicable state legislation or a municipal charter.

8) The Land Use Element

The land use element shows the general distribution, location and characteristics of current and future land uses and urban form. In the past, comprehensive plans included colour coded maps showing exclusive land use categories, such as residential, commercial, industrial, institutional, community facilities, open space, recreational and agricultural uses. Many communities today use sophisticated land use and land cover inventories and mapping techniques, employing Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and new land use and land cover classification systems.

These new systems are better able to accommodate the multidimensional realities of urban form, such as mixed use and time-of-day/seasonal-use changes. Form and character are increasingly being used as important components of land use planning, integrating the many separate components into an integrated land use form.

9) Future Land Use Map

Future land uses, their intensity and density are shown on a future land use map. The land use allocations shown on the map must be supported by land use projections linked to population and economic forecasts for the surrounding region and tied to the assumptions in a regional plan, if one exists. Such coordination ensures that the plan is realistic. The assumptions used in the land use forecasts, typically in terms of net density, intensity, other standards or ratios or other spatial requirements or physical determinants are a fundamental part of the land use element. This element must also show lands that have development constraints, such as natural hazards.

10) Land Use Projections

The land use element should envision all land use needs for a 20-year period (or the chosen time frame for the plan) and all these needs should be designated on the future land use plan map. If this is not done, the local government may have problems carrying out the plan. For example, if the local government receives applications for zoning changes to accommodate uses the plan recognizes as needed, the locations where these changes are requested are consistent with what is shown on the land use plan map.

11) The Transportation Element

The modern transportation element commonly addresses traffic circulation, transit, bicycle routes, ports, airports, railways, recreation routes, pedestrian movement and parking. The exact content of a transportation element differs from community to community depending on the transportation context of the community and region. Proposals for transportation facilities occur against a backdrop of federally required transportation planning at the state and regional levels.

The transportation element considers existing and committed facilities and evaluates them against a set of service levels or performance standards to determine whether they will adequately serve future needs. Of the various transportation facilities, the traffic circulation component is the most common and a major thoroughfare plan is an essential part of this. It contains the general locations and extent of existing and proposed streets and highways by type, function and character of improvement.

12) Street Performance

In determining street performance and adequacy, planners are employing other approaches in addition to or instead of level-of-service standards that more fairly measure a street’s performance in moving pedestrians, bikes, buses, trolleys and light rail and for driving retail trade, in addition to moving cars. This is especially true for urban centres, where several modes of travel share the public realm across the entire right-of-way, including adjacent privately owned “public” spaces. Urban design plans for the entire streetscape of key thoroughfares can augment the transportation element. In addition, it is becoming increasingly common for the traffic circulation component of a comprehensive plan to include a street connectivity analysis. The degree to which streets connect with each other affects pedestrian movement and traffic dispersal.

13) Thoroughfare Plan

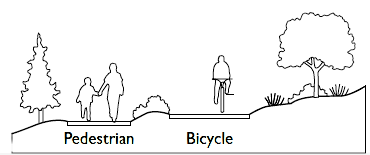

The thoroughfare plan, which includes a plan map, is used as a framework for roadway rehabilitation, improvement and signalization. It is a way of identifying general alignments for future circulation facilities, either as part of new private development or as new projects undertaken by local government. Other transportation modes should receive comparable review and analysis, with an emphasis on needs and systems of the particular jurisdiction and on meeting environmental standards and objectives for the community and region. Typically, surface and structured parking, bikeways and pedestrian ways should also be covered in the transportation element.

14) Transit

A transit component takes into consideration bus and light rail facilities, water-based transit (if applicable) and intermodal facilities that allow transportation users to transfer from one mode to another. The types and capacities of future transit service should be linked to work commute and non-work commute demands as well as to the applicable policies and regulations of the jurisdiction and its region.

15) The Transportation/Land Use Relationship

The relationship between transportation and land use is better understood today and has become a dominant theme in the transportation element. For instance, where transit exists or is proposed, opportunities for transit oriented development should be included; where increased densities are essential, transit services might need to be improved or introduced. This would also be covered in the land use element.

16) Community Facilities Element

The term “community facilities” includes the physical manifestations of governmental or quasi-governmental services on behalf of the public. These include buildings, equipment, land, interests in land, such as easements and whole systems of activities. The community facilities element requires the local government to inventory and assess the condition and adequacy of existing facilities and to propose a range of facilities that will support the land use element’s development pattern. The element may include facilities operated by public agencies and those owned and operated by for-profit and not-for-profit private enterprises for the benefit of the community, such as privately owned water and gas facilities or museums.

Some community facilities have a direct impact on where development will occur and at what scale water and sewer lines, water supply and wastewater treatment facilities. Other community facilities may address immediate consequences of development. For example, a storm water management system handles changes in the runoff characteristics of land as a consequence of development. Still other facilities are necessary for the public health, safety and welfare, but are more supportive in nature. Examples in this category would include police and fire facilities, general governmental buildings, elementary and secondary schools. A final group includes those facilities that contribute to the cultural life or physical and mental health and personal growth of a local government’s residents. These include hospitals, clinics, libraries and arts centres.

17) Operation by Other Public Agencies

Some community facilities may be operated by public agencies other than the local government. Such agencies may serve areas not coterminous with the local government’s boundaries. Independent school districts, library districts and water utilities are good examples. In some large communities, these agencies may have their own internal planning capabilities. In others, the local planning agency will need to assist or coordinate with the agency or even directly serve as its planner.

18) Parks, Open Space and Cultural Resources

A community facilities element may include a parks and open space component. Alternatively, parks and open space may be addressed in a separate element. The community facilities element will inventory existing parks by type of facility and may evaluate the condition of parks in terms of the population they are expected to serve and the functions they are intended to carry out. To determine whether additional parkland should be purchased, population forecasts are often used in connection with population based needs criteria (such as a requirement of so many acres of a certain type of park within a certain distance from residents).

Other criteria used to determine parkland need may include parkland as a percentage of land cover or a resident’s proximity to a park. Open space preservation may sometimes be addressed alone or in connection with critical and sensitive areas protection and agricultural and forest preservation. Here the emphasis is on the ecological, scenic and economic functions that open space provides. The element may also identify tracts of open land with historic or cultural significance, such as a battlefield. The element will distinguish between publicly held land, land held in private ownership subject to conservation easements or other restrictions and privately owned parcels of land subject to development.

19) The Housing Element

The housing element assesses local housing conditions and projects future housing needs by housing type and price to ensure that a wide variety of housing structure types, occupancy types and prices (for rent or purchase) are available for a community’s existing and future residents. There may currently be a need for rental units for large families or the disabled or a disproportionate amount of income may be paid for rental properties. Because demand for housing does not necessarily correspond with jurisdictional boundaries and the location of employment, a housing element provides for housing needs in the context of the region in which the local government is located.

20) Jobs/Housing Balance

The housing element can examine the relationship between where jobs are or will be located and where housing is or will be available. The jobs/housing balance is the ratio between the expected creation of jobs in a region or local government and the need for housing expressed as the number of housing units. The higher the jobs/housing ratio, the more jobs the region or local government is generating relative to housing. A high ratio may indicate to a community that it is not meeting the housing needs (in terms of either affordability or actual physical units) of people working in the community.

21) Housing Stock

The housing element typically identifies measures used to maintain a good inventory of quality housing stock, such as rehabilitation efforts, code enforcement, technical assistance to homeowners and loan and grant programs. It will also identify barriers to producing and rehabilitating housing, including affordable housing. These barriers may include lack of adequate sites zoned for housing, complicated approval processes for building and other development permits, high permit fees and excessive exactions or public improvement requirements.

22) The Economic Development Element

An economic development element describes the local government’s role in the region’s economy, identifies categories or particular types of commercial, industrial and institutional uses desired by the local government and specifies suitable sites with supporting facilities for business and industry. It has one or more of the following purposes.

- Job creation and retention

- Increases in real wages (e.g. economic prosperity)

- Stabilization or increase of the local tax base

- Job diversification (making the community less dependent on a few employers)

A number of factors typically prompt a local economic development program. They include loss or attraction of a major employer, competition from surrounding communities or nearby states, the belief that economic development yields a higher quality of life, the desire to provide employment for existing residents who would otherwise leave the area, economic stagnation or decline in a community or part of it, or the need for new tax revenues. An economic development element typically begins with an analysis of job composition and growth or decline by industry sector on a national, state wide or regional basis, including an identification of categories of commercial, industrial and institutional activities that could reasonably be expected to locate within the jurisdiction.

It will also examine existing labour force characteristics and future labour force requirements of existing and potential commercial and industrial enterprises and institutions in the state and the region in which the local government is located. It will include assessments of the jurisdiction’s and the region’s access to transportation to markets for its goods and services and its natural, technological, educational and human resources. Often, an economic development element will have targets for growth, which may be defined as number of jobs or wages or in terms of targeted industries and their land use, transportation and labour force requirements.

The local government may also survey owners or operators of commercial and industrial enterprises and inventory commercial, industrial and institutional lands within the jurisdiction that are vacant or significantly underused. An economic development element may also address organizational issues, including the creation of entities, such as non-profit organizations, that could carry out economic development activities.

23) The Critical and Sensitive Areas Element

Some comprehensive plans address the protection of critical and sensitive areas. These areas include land and water bodies that provide habitat for plants and wildlife, such as wetlands, riparian corridors and floodplains; serve as groundwater recharge areas for aquifers; and areas with steep slopes that are easily eroded or unstable. They also can include visually, culturally and historically sensitive areas. By identifying such areas, the local government can safeguard them through regulation, incentives, purchase of land or interests in land, modification of public and private development projects or other measures.

24) Natural Hazards Element

Natural hazards elements document the physical characteristics, magnitude, severity, frequency, causative factors and geographic extent of all natural hazards. Hazards include flooding, seismic activity, wildfires, wind related hazards such as tornadoes, coastal storms, winter storms and hurricanes and landslides or subsidence resulting from the instability of geological features. A natural hazards element characterizes the hazard, maps its extent, if possible, assesses the community’s vulnerability and develops an appropriate set of mitigation measures, which may include land use policies and building code requirements. The natural hazards element may also determine the adequacy of existing transportation facilities and public buildings to accommodate disaster response and early recovery needs such as evacuation and emergency shelter. Since most communities have more than one type of hazard, planners should consider addressing them jointly through a multi hazards approach.

25) The Agriculture Element

Some comprehensive plans contain agriculture and forest preservation elements. This element focuses on the value of agriculture and forestlands to the local economy, although it can also include open space, habitat and scenic preservation. For such an element, the local government typically inventories agriculture, forestland and ranks the land using a variety of approaches. It then identifies conflicts between the use of such lands and other proposed uses as contained in other comprehensive plan elements.

For example, if an area were to be preserved for agricultural purposes, but the community facilities element proposed a sewer trunk line to the area, that would be a conflict, which if not corrected would result in development pressure to the future agricultural area. Implementation measures might include agricultural use valuation coupled with extremely large lot requirements, transfer of development rights, purchase of development rights, conservation easements, marketing programs to promote the viability of local agricultural land and programs for agricultural based tourism.

Implementation of Comprehensive Plan

A local comprehensive plan must contain an implementation program to ensure that the proposals advanced in the plan are realized. Sometimes referred to as an “action plan,” the implementation program includes a list of specific public or private actions organized by their scheduled execution date such as short term (1 to 3 years), medium term (4 to 10 years) and long term (11 to 20 years) actions. Typical actions include capital projects, changes to land development regulations and incentives, new programs or procedures, financing initiatives and similar measures. Each listed action should assign responsibility for the task and include an estimate of cost and a source of funding. Some communities produce comprehensive plans that are more broadly based and policy driven. These plans will require a less detailed implementation program. The individual functional plans produced as a result of the comprehensive plan address the assignment of costs or specific tasks.